I didn’t manage to cover, as I originally planned to

do, all the parties involved in the Helsinki city council election, at least

not before election day itself, this past Sunday.

So, for the sake of tying up loose threads, I’m going to briefly mention the seven plus parties that also ran.

Liberaalipuolue, (The Liberal Party). This is another one of those very minor parties, and a new one. It was registered as a formal party only last year, after existing briefly as an unofficial protest group called the “Whiskey Party”. I’m guessing by its slogan Vapaus valita (“Freedom to Choose”), that it has a libertarian bent. It won no seats on the council.

Itsenäisyyspuolue or IPU, (The Independence Party). Another small, fringe party, whose main program is Finland’s exiting the EU. It won no seats.

Perussuomalaiset, (The True Finns). This party has gained some international attention as one of those rising anti-immigrant, xenophobic, EU-skeptic right-wing parties, like France’s National Front or UKIP. It seems, however, that PS is rising no longer.

In a US context, PS wouldn’t be seen as so completely right-wing, in the sense that it has no desire to touch Finland’s generous welfare system, a system which any right-thinking American conservatives would recoil at as being “socialist”. PS would probably argue that it’s safeguarding the social welfare system -- by keeping unwanted and undeserving immigrants from accessing it. It may not be a winning argument.

In the Helsinki city council PS lost two of its previous eight seats. Its municipal support in the country overall dropped by 3.5%, making it this election’s biggest loser.

Svenska folkpartiet i Finland, (Swedish People’s Party of Finland). This is the party that has traditionally advocated for the interests of Swedish speakers, Finland largest linguistic minority (about five percent of the country). Other than protecting the official status of the Swedish language in the public sphere, the party has a broadly liberal agenda that no doubt attracts the votes of some non-Swedish speakers. The party retained its five seats (eller, dess fim platser).

Suomen Keskusta, (The Central Party of Finland). This is one of the three major parties nationwide, along with Kokoomus and the Social Democrats. It is basically an agrarian party, so naturally its support base is concentrated in the countryside. Urban Helsinki, no so much. The party lost one of the three seats it held in the last council.

Kansallinen Kokoomus, (The National Coalition Party). Finland’s pro-business party, which you might think makes it analogous to the American Republicans, or at least old fashioned “Country Club” Republicans. That is, it’s pro-business without the social conservativism and anti-government obsessions of modern-day Republicans.

Kokoomus gained two seats in Sunday’s elections, strengthening its position as the council’s biggest party with 25 seats.

Vihreä liitto, (The Green League). The Greens, a well-established, yet relatively young party (30-years-old, this year), was the big winner in the election, increasing its support nationwide by almost 4%, the most of any party, and adding three seats in Helsinki, bringing it to 21.

It is, naturally enough, a party dedicated to environmental and human-rights issues.

Otherwise in the election, the SDP lost 3 seats, holding its position as the third-biggest party, with 12 seats. Vasemmisto gained one seat, bringing it up to ten. The Feminist party won its first ever seat, as did the Pirate Party.

The Christian Democrats kept its two seats, though one will now be filled by Keskusta politician Paavo Väyrynen, whom I was earlier shocked to see on the Christian Dems list. I have since learned that Väyrynen joined the CD list after Keskusta refused to allow him to run in his native Lapland. The move seemed to work out for him.

Parties that won not even a single seat were the marginal leftist parties the Communist Workers’ Party and the Communist Party of Finland, which lost the one seat it did have.

Some parties I’d never even heard of, such as the Suomen Eläinoikeuspuolue (Animal Rights Party) and Edistyksellistä Helsinkiä (Progressive Helsinki) also got no seats.

I’m happy to say voter turnout in my neighborhood was 71.8%, better than the 61.6% for Helsinki overall. We are some politically engaged folks around here!

So, for the sake of tying up loose threads, I’m going to briefly mention the seven plus parties that also ran.

Liberaalipuolue, (The Liberal Party). This is another one of those very minor parties, and a new one. It was registered as a formal party only last year, after existing briefly as an unofficial protest group called the “Whiskey Party”. I’m guessing by its slogan Vapaus valita (“Freedom to Choose”), that it has a libertarian bent. It won no seats on the council.

|

| The Liberal Party. "Cheaper housing, freer Helsinki." |

Itsenäisyyspuolue or IPU, (The Independence Party). Another small, fringe party, whose main program is Finland’s exiting the EU. It won no seats.

|

| The Independence Party. "Decision-making close, humanity the priority." |

Perussuomalaiset, (The True Finns). This party has gained some international attention as one of those rising anti-immigrant, xenophobic, EU-skeptic right-wing parties, like France’s National Front or UKIP. It seems, however, that PS is rising no longer.

In a US context, PS wouldn’t be seen as so completely right-wing, in the sense that it has no desire to touch Finland’s generous welfare system, a system which any right-thinking American conservatives would recoil at as being “socialist”. PS would probably argue that it’s safeguarding the social welfare system -- by keeping unwanted and undeserving immigrants from accessing it. It may not be a winning argument.

In the Helsinki city council PS lost two of its previous eight seats. Its municipal support in the country overall dropped by 3.5%, making it this election’s biggest loser.

|

| True Finns. "Your vote worth it, because of True Finns" |

Svenska folkpartiet i Finland, (Swedish People’s Party of Finland). This is the party that has traditionally advocated for the interests of Swedish speakers, Finland largest linguistic minority (about five percent of the country). Other than protecting the official status of the Swedish language in the public sphere, the party has a broadly liberal agenda that no doubt attracts the votes of some non-Swedish speakers. The party retained its five seats (eller, dess fim platser).

|

| The Swedish People's Party. "Near you in Helsinki." |

Suomen Keskusta, (The Central Party of Finland). This is one of the three major parties nationwide, along with Kokoomus and the Social Democrats. It is basically an agrarian party, so naturally its support base is concentrated in the countryside. Urban Helsinki, no so much. The party lost one of the three seats it held in the last council.

|

| Keskusta. "Caregivers in Helsinki." |

Kansallinen Kokoomus, (The National Coalition Party). Finland’s pro-business party, which you might think makes it analogous to the American Republicans, or at least old fashioned “Country Club” Republicans. That is, it’s pro-business without the social conservativism and anti-government obsessions of modern-day Republicans.

Kokoomus gained two seats in Sunday’s elections, strengthening its position as the council’s biggest party with 25 seats.

|

| Kokoomus. "The makers of Helsinki's future." |

Vihreä liitto, (The Green League). The Greens, a well-established, yet relatively young party (30-years-old, this year), was the big winner in the election, increasing its support nationwide by almost 4%, the most of any party, and adding three seats in Helsinki, bringing it to 21.

It is, naturally enough, a party dedicated to environmental and human-rights issues.

|

| The Greens. "Together a better Helsinki." |

Otherwise in the election, the SDP lost 3 seats, holding its position as the third-biggest party, with 12 seats. Vasemmisto gained one seat, bringing it up to ten. The Feminist party won its first ever seat, as did the Pirate Party.

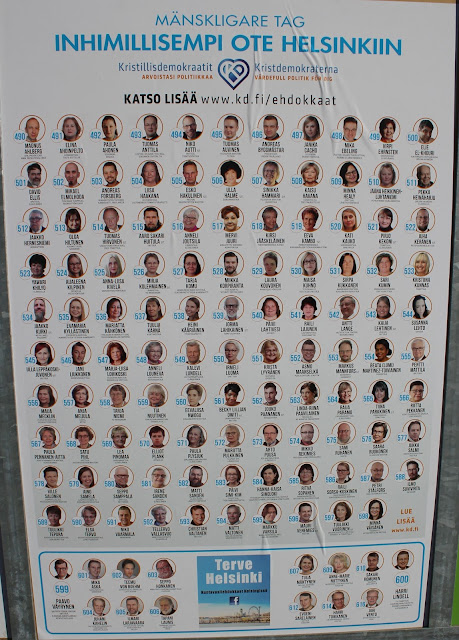

The Christian Democrats kept its two seats, though one will now be filled by Keskusta politician Paavo Väyrynen, whom I was earlier shocked to see on the Christian Dems list. I have since learned that Väyrynen joined the CD list after Keskusta refused to allow him to run in his native Lapland. The move seemed to work out for him.

Parties that won not even a single seat were the marginal leftist parties the Communist Workers’ Party and the Communist Party of Finland, which lost the one seat it did have.

Some parties I’d never even heard of, such as the Suomen Eläinoikeuspuolue (Animal Rights Party) and Edistyksellistä Helsinkiä (Progressive Helsinki) also got no seats.

I’m happy to say voter turnout in my neighborhood was 71.8%, better than the 61.6% for Helsinki overall. We are some politically engaged folks around here!